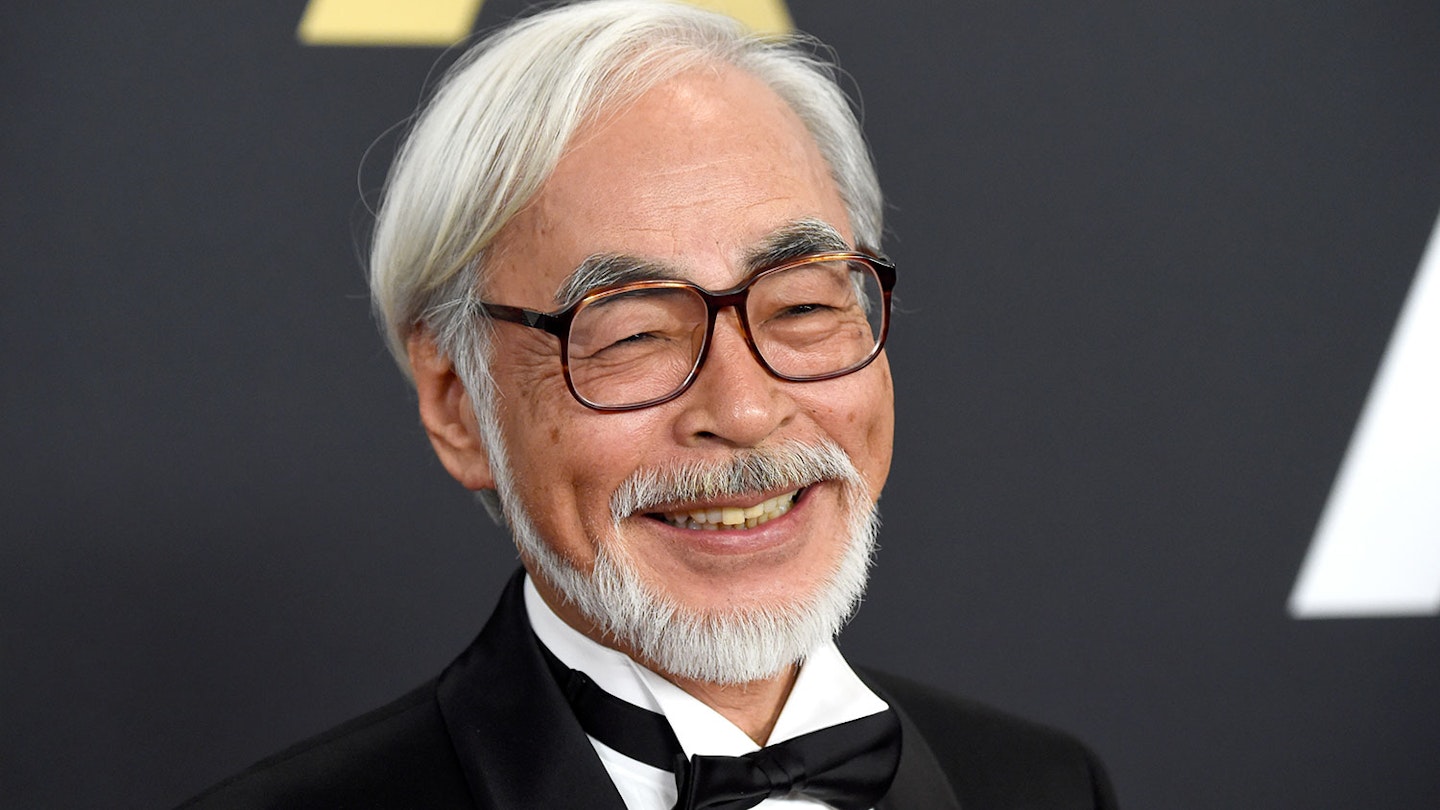

As it turns out, Hayao Miyazaki simply cannot stop. The legendary Japanese animator — co-founder of Studio Ghibli; master of fantasy anime; creator of Totoro, Kiki, Ponyo, No-Face, Soot Sprites, the Catbus and many more — intended to retire following 2013’s The Wind Rises, his elegiac World War II plane drama. It wasn’t the first time. He also meant to retire after 1997’s epic war fable Princess Mononoke; and again after 2001’s global breakout Spirited Away. Every time, he returned with a film that he couldn’t not have made, one whose existence almost demanded itself. The Boy And The Heron is no different.

A decade after his paean to the power of flight and the corruptibility of dreams, Miyazaki returns with another outright masterwork — this time, the kind of rich, bewildering, ceaselessly imaginative fantasy-adventure that Ghibli is best known for. The Boy And The Heron is not only a victory lap for a filmmaker long regarded as one of the greatest of all time — it’s a contemplative and self-reflective psychological dive into the mind of its own creator, a soul laid bare in cinematic form. If that sounds heavy — and at points, it is — it’s also thrillingly adventurous, spikily funny, and beautifully crafted, a feast for the eyes, mind, heart and soul. A Miyazaki movie, then.

A Greatest Hits set of Hayao Miyazaki's distinctive fantasy output.

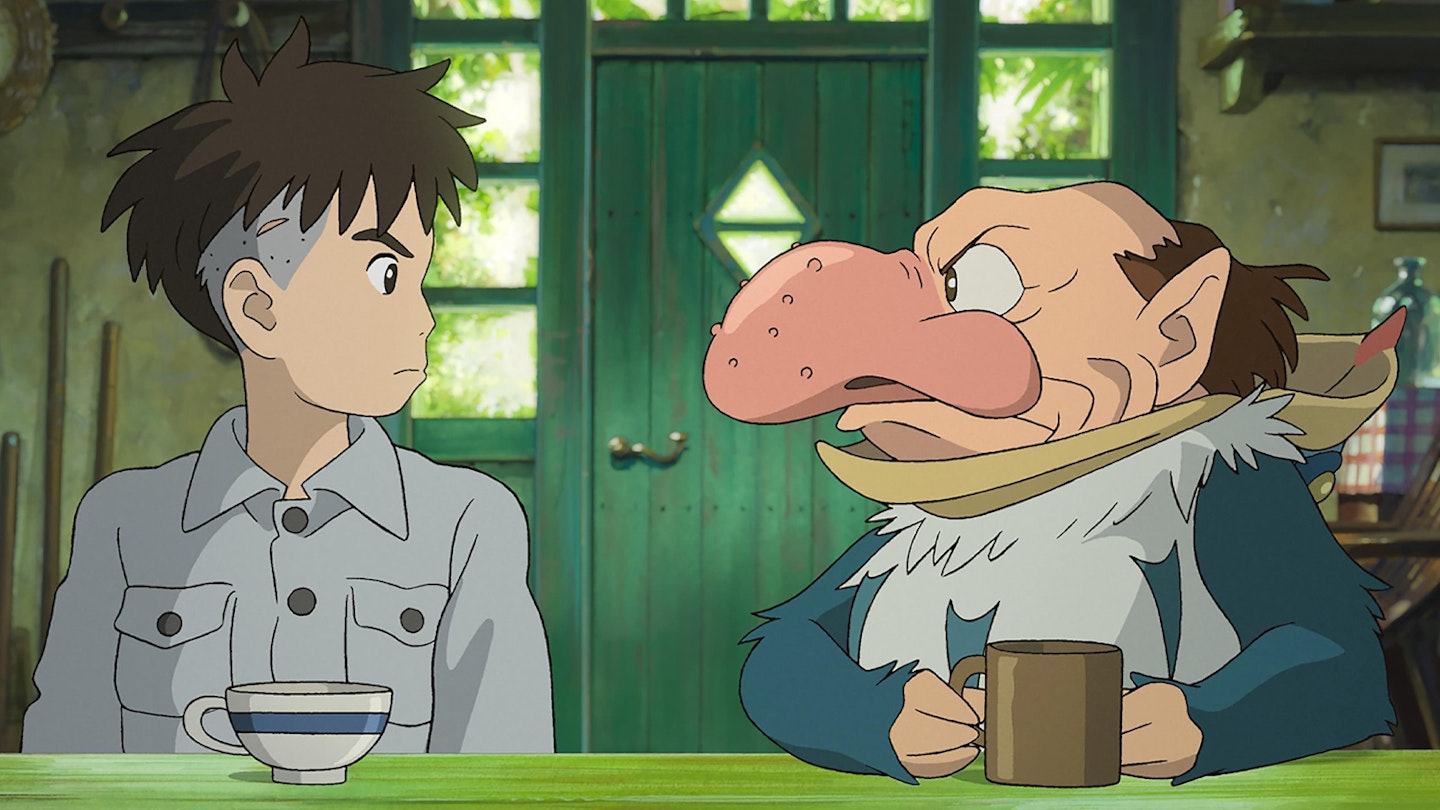

Where The Wind Rises was curious for largely eschewing Miyazakian mythology in favour of historical drama, The Boy And The Heron complements it as a Greatest Hits set of the director’s distinctive fantasy output. This, too, is set amid the destruction of World War II — in its early scenes, Miyazaki paints the devastation of young Tokyo boy Mahito’s home (and the death of his mother) in an impressionistic flurry of flickering flame, some of the studio’s most striking animation ever. From there, it moves out to the countryside — playing like a dark relative of My Neighbour Totoro — as Mahito is re-homed at his new mother’s rural estate. A baby is on the way. His father has his head buried in his munitions work. A gaggle of elderly maids won’t leave him alone. And a talking grey heron keeps, well, talking to him.

For its first hour, The Boy And The Heron unfolds at a gentle pace, Mahito coming to terms with his new life — though his quiet pastoral existence is punctuated by outbursts of grief-fuelled anger and the menacing encroachment of the heron, who taunts him with cryptic messages and ominous warnings. As with all of Miyazaki’s work, it’s peppered with beautifully small humanistic moments, incidental actions purposefully animated that make the characters feel truly alive. And even in its quieter half, there is mesmeric imagery: a chorus of carp rising from a lake, mouths agape; the heron’s steely gaze, accompanied by staccato piano notes from Joe Hisaishi’s stunning score; a mass of toads crawling up Mahito’s body.

But it’s in its wilder, wandering second half that The Boy And The Heron really takes off, once the heron draws Mahito into a perilous fantasy realm bursting with boundless invention. The pair become an unlikely double act on an existential quest (there are thematic shades of Pan’s Labyrinth here) to save mothers both past and present — a journey towards emotional revelation, travelling not just through wondrous worlds (a ghoul-strewn seafaring town; a castle ruled by oversized birds; a plain overseen by an ancient wizard), but through the halls of Miyazaki’s whole career. The film’s dark and dangerous fantasy impulses hew close to Princess Mononoke; its hallucinatory coming-of-age allegory is in the Spirited Away vein; the breathtakingly adorable warawara are the cutest Ghibli creation since the Ponyo babies; the lushly overgrown kingdom is akin to Laputa; the anthropomorphic parakeets are rich in Totoro DNA. But for all the familiarity, it feels fearlessly new too, always moving in unexpected ways.

Even Miyazaki’s long-fostered narrative idiosyncrasies are feature as much as bug here — the free-wheeling story will likely bemuse newcomers (advised to begin their Ghibli journey elsewhere), but be familiar to fans of Spirited Away or Howl’s Moving Castle. Its rather abrupt ending, too, is almost Ghibli tradition at this point.

It’s impossible not to view the film as a kaleidoscopic self-portrait. This is Miyazaki as lonely boy, and cantankerous heron, and wise old wizard, ruminating on his kingdom of dreams and madness, wary of it toppling or falling into the wrong hands. It’s a story about what it takes to create the world we want to live in, all wrapped up in the kind of film the world undoubtedly needs. Now that The Boy And The Heron exists, you can’t imagine Miyazaki not making it. We’re lucky to have it.