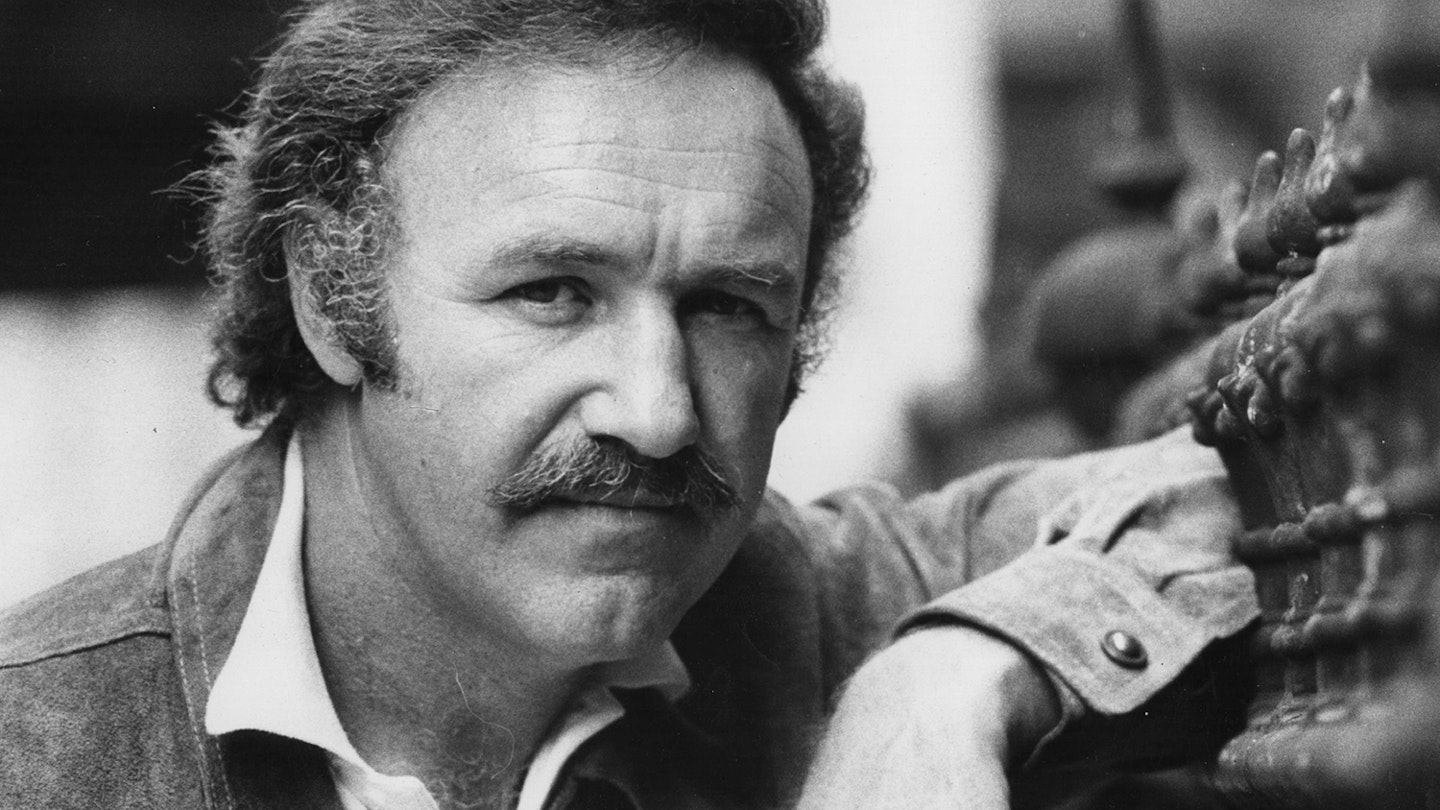

It’s been sixteen years since Gene Hackman was last seen on screen. The Hollywood legend – who appeared in everything from Superman The Movie, to The French Connection, to The Conversation and The Royal Tenenbaums – retired from acting back in the early 00s. But in 2009, Empire was granted a rare interview with the screen icon, talking his glorious career and the novel-writing he turned to after leaving the silver screen behind. Here, to mark his 90th birthday, is the original feature in full.

Donald Petrie’s 2004 comedy, Welcome To Mooseport, in which a former US president faces off against a small town loudmouth for the role of Mayor, is the sort of amiable, low-rent affair that features a couple of laughs, decent performances and which you manage to forget even as you’re watching it. It tanked in the States, taking in just $16 million. You’d be hard pushed to find anyone who owns, or will admit to owning, a copy. Yet, in its own way, it’s a piece of movie history.

Not because it was the first (and, mercifully, last) attempt by foghorn-voiced charisma-deficient comedian, Ray Romano, to kickstart a live-action movie career, but because it marks the last on-screen appearance of the legendary Gene Hackman. And this is how he bowed out:

Former US President and newly-elected Mooseport mayor, Monroe Cole (that would be Hackman) is in love with his executive secretary, Grace (Marcia Gay Harden), except, dammit, he’s not man enough to tell her. So she’s off, forever, on a plane. Except the plane won’t take off – and then, lo and behold, here comes President Cole, getting down on his knees, making beseeching exhortations of commitment (“no salt”), and then winning her over with the sort of smacker that suggests he hasn’t eaten in many days.

Grace bats her eyelids. “How do you know my plane wouldn’t take off?” she says. Hackman smiles, that familiar old wily grin that lights up his eyes. “Turns out that I have a little bit of pull here at this airport now.” The crowd cheer and congratulate the happy couple – he leans in and pulls Harden close and…

Then Petrie, the journeyman clod, cuts away from the two-time Oscar-winning bona fide legend to the star of deeply average and erroneously-titled shitcom, Everyone Loves Raymond, and that’s that. Soon after that, Hackman retired from acting, with the quiet grace and dignity that had epitomised his astonishing 40-year career. There was no announcement. There was no press release. He just slipped away into the anonymity of life with his wife, Betsy Arakawa.

“The doctor advised me that my heart wasn’t in the kind of shape that I should be putting it under any stress.”

It’s tempting to speculate on the reasons for Hackman’s retirement – afterall, Sean Connery retired from acting around the same age (both men are 79) and time (2003 for the former 007) as Hackman, because of a blow-out with director Stephen Norrington on the set of The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen. A mischievous person might suggest that Hackman had perhaps watched Welcome To Mooseport and concluded, ‘what’s the point?’

But there were no shenanigans involved in Hackman’s decision. Instead, the truth is more prosaic and sobering than that. “The straw that broke the camel’s back was actually a stress test that I took in New York,” says Hackman, talking exclusively to Empire from his home in Santa Fe. “The doctor advised me that my heart wasn’t in the kind of shape that I should be putting it under any stress.”

But some men aren’t built to sit around at home doing jigsaw puzzles, or watching whatever the American equivalent of Come Dine With Me is. Admittedly, Hackman has his little home comforts – watching “DVDs that my wife rents; we like simple stories that some of the little low-budget films manage to produce”, while every Friday night is set aside for a Comedy Channel marathon, with particular attention paid to Eddie Izzard (“The speed of thought is amazing”). He likes to fish, and paint, something he’s done for countless years (and with a great deal of proficiency, too).

But all that extra time on his hands had to be filled, so Hackman threw himself headlong into a secondary career as an author. Well, co-author, to be exact, teaming up with his neighbour and friend, Daniel Lenihan, on a series of historical adventure novels. And, in a way, to say that it’s a brand-new career is somewhat disingenuous. After all, the first, Wake Of The Perdido Star, came out in 1999, when Hackman was still making flicks like Under Suspicion and The Replacements, while the second, the courtroom drama Justice For None, was released in 2004, just after Hackman had hung up his acting spurs.

But Hackman’s retirement gave the pair licence to really dedicate themselves to the cause, and their third, and most recent, collaboration – Escape From Andersonville: A Novel Of The Civil War – is just about to come out in the UK. A robustly-written, rousing tale of a Confederate officer attempting to rescue his men from the Andersonville prison camp, a hideous morass of human decay that claimed the lives of 12,000 men in just under a year, it won’t win any Booker Prizes, but it’s a fun read, with some nicely-drawn characters, a sense of genuine pace and place, and a contender for weird-out of the year: a sex scene co-written by Popeye Doyle, containing the immortal line: “His sex hung between his legs like a sack of hot lead…” It’s the written equivalent of walking in on your parents doing it.

“It’s very relaxing for me,” says Hackman of the writing process. “I don’t picture myself as a great writer, but I really enjoy the process, especially on this book. We had to do a great deal of research on it to get some of the facts right, and it is stressful to some degree, but it’s a different kind of stress. It’s one you can kind of manage, because you’re sitting there by yourself, as opposed to having ninety people sitting around waiting for you to entertain them!”

In a way, Hackman grew into words. His father was a printer on the local newspaper, the Commercial-News in Danville, Illinois, while both his grandfather and uncle were reporters. So becoming a writer would seem like a natural development. Yet, a cursory glance at his voluminous CV reveals that, over the course of a career that spanned some 44 years and 80 films, not once does Hackman’s name appear as a writer. Not for the lack of trying, mind you. After all, if there’s one thing that a pre-PlayStation generation actor can do while noodling around in his trailer, waiting for his close-up, then it’s sit down at his desk and put some thoughts down on paper.

“I wrote a lot of little short pieces, almost like audition pieces, for actors,” he recalls. “My son thought he wanted to be an actor at one time and was in New York and I wrote him a couple of little monologues. I guess that’s where I started. I really enjoyed it. Ideas would just pop into my head and I would write them down.”

There’s a tremendous difference between writing for fun, or writing something that you know only a handful of people will hear or read, and writing something that could be experienced by millions. That was Hackman’s next step – in the late ‘80s, he bought the rights to a best-selling crime novel, and set about the tricky task of adapting it himself, with a view to possibly directing and playing the standout role of a psychopathic killer who specialises in playing mindgames with the Feds from inside his prison cell. “I was so respectful of the book that I was into it 100 pages, and had about 300 pages of the script!” says Hackman, his laugh sounding exactly like it does on film; a warm and cheeky chuckle from the back of the throat. “So I could see that I didn’t have the experience to do that kind of thing at that point, so I let the project go, kinda regretfully.”

Small wonder, for the project was The Silence Of The Lambs which, in case you didn’t know, went on to gross $273 million worldwide, become an enduring classic and win Oscars for Jonathan Demme, Ted Tally and Anthony Hopkins in the categories that Hackman had earmarked for himself – directing, writing and the role of Hannibal Lecter. “At least I had a good eye for the material,” laughs Hackman who, with two Oscars on his mantelpiece already, can afford to be sanguine about the experience. “I really wasn’t very inventive about the process. I was more concerned about the description of the scene process, and it just got to be overlong. I didn’t think within the time I had on the option I had bought on the thing, that I could develop it properly.”

Bowed, but not broken by his incompatibility with the strictures of a screenplay, Hackman gave it another go, adapting a book called Ada Blackjack: A True Story Of Survival In The Arctic. “It was the true story of an Inuit woman who had gone on an expedition in the Arctic, and everybody on the expedition had died,” he explains. “She was on her own for six months up there – it was kind of a fascinating story in some ways, but I couldn’t quite lick it. I couldn’t quite get it to come alive. I didn’t have any confidence in it.”

That lack of confidence in his writing might explain why, when Hackman finally decided to pick up a pen (he writes longhand, and his wife gets it all typed up) again, he didn’t go it alone. When he was preparing to star alongside Tom Cruise in The Firm, and needed to learn how to scuba dive, he was put in touch with Lenihan, a local marine biologist and accomplished diver. “In Santa Fe, there’s not a lot of scuba diving,” chuckles Hackman. “But Daniel took me to this public swimming pool – it had a depth of nine feet or something like that – and I got my first introduction to scuba through him.”

From there, the two got chatting about authors they liked – Melville, Hemingway, “all the traditional adventure type writers” – and tentatively decided to try writing together. “I said to him, ‘Hey, I’ve never written anything…’” says Hackman. “So I went home and I made up a scene about a young man up in the sheets in a forerigged sailing ship in a storm, and that was the start of it.”

That became the basis for The Wake Of The Perdido Star, and the formation of an unusual writing process, whereby they would each write separate chapters, focusing on a particular character, so in Escape From Andersonville, Lenihan would focus on the lead, Nathaniel Parker, while Hackman would write chapters featuring the roguish Southern soldier, Marcel La Farge. They also learned never to write in the same room. “The process grew out of some long, painful nights of pounding away at this partnership,” admits Hackman. “We had a good writing relationship, though.”

“One asks oneself questions as an actor like, ‘where am I coming from? Where am I going? What do I want?’ Those three simple things can carry you a long way as an actor. As a writer, you can start the same way.”

Emphasis on ‘had’, for the partnership has been dissolved, with Lenihan moving onto non-fiction projects, while Hackman is venturing out on his own, with a Western. “I like it a lot,” he says of being on his lonesome. “There’s times when I wish I had another hundred and fifty pages to go, that someone could come in and slot something in there, but generally speaking, I like that.”

For Hackman, the parallels between acting and writing are obvious. “I think it was a natural transition,” he recalls. “One asks oneself questions as an actor like, ‘where am I coming from? Where am I going? What do I want?’ Those three simple things can carry you a long way as an actor. As a writer, you can start the same way.”

It’s tempting to suggest that writing is a dream for an actor, in that he can conjure up an array of different characters and, in essence, ‘play’ them – a notion that Hackman admits has some credence. “I would have liked to, in the early days,” he says. “I didn’t have the looks for that kind of leading man part, but that era was already gone by the time I got into movies in the Fifties. So I kinda regret that I didn’t have the chance to participate in some of those things.” So it’s easy to see, then, that characters like the dark and mysterious La Farge as a great lost Hackman part; you may even want to picture Hackman in your head when you’re reading the book, although the author prefers you visualize a more glamorous model.

“It goes back to the old days of Errol Flynn and James Cagney, the adventure movies that were done in the 30s,” he says. “That kind of roguish, handsome, devil-may-care kind of character that’s fun to write. We don’t see a lot of that kind of thing in movies any longer. Unfortunately, things have gotten darker and more slick, in one way or another, and I miss that in a funny kind of way.”

On several occasions during our forty-minute conversation, Hackman expresses a similar sentiment. It’s not quite ‘it were all fields round here in my day’, but it’s not far off. With that, and the fact that his three novels have all been of a historical bent, you’d imagine that Hackman is a man who loves to talk about the past. You’d be wrong.

Now and again, something will shine through, like a recollection of research made with Al Pacino on the little-seen 1973 movie, Scarecrow – “Al and I got to do spent about a week in San Francisco, just hanging out in the Tenderloin area and we got to know some of the life of guys who were similar to the characters we played in the movie, kinda bums. That was kinda fun.” Otherwise, for the most part, Hackman would seem to be suffering from a case of the proverbial past-is-prologues. At one point, Empire asks him if it’s a coincidence whether Escape From Andersonville features a ‘leave no man behind’ plot that has featured in at least three of Hackman’s movies – the unloved, but actually pretty damn enjoyable trilogy of Bat 21, Behind Enemy Lines and Uncommon Valour. There’s a pause while he accesses his internal RAM. “You know, if you were to ask me what those three movies were, I would be surprised!”

So, instead, allow us to recall his career; one so remarkable and filled with great work that it can easily be ranked up there with that of his great hero, Marlon Brando. Run your eye over his CV, and the great films and performances come tumbling out. The brittle, walled-in Harry Caul in Coppola’s The Conversation. The swaggering Lex Luthor in Superman The Movie and Superman II. The twinkling, roguish Royal Tenenbaum in, well, The Royal Tenenbaums. The loathsome Little Bill Daggett in Unforgiven, the role that would give him his second Oscar in 1992. The first, of course, came for The French Connection and his unforgettable bottling of the human lightning, Popeye Doyle, fiery, irascible, totally committed.

There are the great moments, too. His speech in the underrated basketball drama, Hoosiers, so inspirational – “Forget about the crowds, the fancy uniforms, and focus on what got us here” - that football managers still use it to this day. The moment in The Poseidon Adventure when Hackman’s heroic Reverend Scott rails against God – “How much more blood?” - before sacrificing himself so that others can live. The hilarious cameo as the blind hermit in Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein, where he shows up for five minutes and nicks the entire film.

Hackman’s gift was that he could take any situation – be it trying to blow up California so that he can make a killing off previously worthless real estate – or any line – “Turns out that I have a little bit of pull here in this airport now” seems like a good candidate – and make it seem utterly, indelibly real. There was no pretension in his work, no sense that he was doing anything other than saying these words for the first time. Lillian Gish would have loved Hackman – for you never, ever, caught him acting. And that’s precisely how he wanted it. Hackman was an advocate of research – “On The French Connection, I had the chance to go to New York about a month before we started shooting, and had a chance to drive around with the cops at night through Harlem. You learn a great deal, and there’s a kind of reality there that set in, that I think is valuable to actors.” But there were times when, as he says, “you just show up and they put the stuff on you and you say your words.”

Hackman’s enduring brilliance was that, for even the most tricky, research-heavy performances, he made it seem as if he’d just shown up, had the stuff put on him, and then said the words. There was a serenity about him that totally justified Delroy Lindo’s wonderfully nonsensical description of his character in David Mamet’s Heist, “my motherfucker’s so cool, when he goes to sleep, sheep count him.”

Of course, if his classmates at the Pasadena Playhouse in California, where Hackman studied acting in his mid-20s, had had their druthers, he’d have gone nowhere, and not even there especially quickly. They voted him, along with a fellow student, Least Likely To Succeed. The fellow student was Hackman’s lifelong friend, Dustin Hoffman. We know what happened to Hackman and Hoffman – the rest of the classmates, with their X-Factor judge’s eyes for talent? Not so much.

But breaking into movies took a while for Hackman. He was 37 by the time he got his big break, with an Oscar-nominated turn in Bonnie & Clyde in 1967. By that point, he and Hoffman and another struggling actor named Robert Duvall had spent plenty of time in New York poverty, helping each other to pick out the splinters they would get from all the doors being slammed in their faces. Not that Hackman was any stranger to adversity – his father left the family home, without warning and only a wave goodbye, when Hackman was 13. Deeply affected by it, Hackman ran away to join the Marines when he was 16. A four-year stint was followed by menial tasks galore, before he tried his hand at acting. And, even as rejection as an actor was hounding him, tragedy hounded him when his mother died, in a house fire, in 1962.

Career-wise, Hackman kept plugging away, and even managed to bag the pivotal role of Mr. Robinson, alongside his old pal Dusty Hoffman, in Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. At least, he bagged it for a while until he was fired and replaced by Murray Hamilton. Who knows what would have happened if he’d kept the role – but he wasn’t given too much time to mope about it before Warren Beatty, with whom Hackman had worked briefly on Lilith, called to offer him a part in Bonnie & Clyde.

An Oscar nomination duly followed, and from there Hackman took off, blazing a trail for leading men who didn’t look like they had just stepped out of a branch of Abercrombie & Fitch. In Hackman’s balding pate and broad features that always seemed crinkled even before age truly set in, we find the antecedents of Paul Giamatti, Phillip Seymour Hoffman and Steve Buscemi, character actors turned leading men and proof positive that talent and heft and gravitas and the ability to deliver a line like you goddamn mean it will find its place alongside gleaming teeth and flashing eyes.

It hasn’t all been plain sailing. It never is. There have been bad movies. There have been new-conservatory jobs. (Superman IV: The Quest For Peace neatly qualifies as both). There have been clashes with directors – rumour has it that Wes Anderson, who wrote Royal Tenenbaum for Hackman and wooed him for months to play the role, and Hackman didn’t get on, with the actor even walking out on at least one occasion, while the story goes that he railed against Sam Raimi, on the set of The Quick And The Dead, when Raimi – for whom actors were then just props that happened to speak and move now and again – wanted to strap a camera to his chest; something that Bruce Campbell would have had no problem with, but two-time Oscar winners are a different breed.

“It’s a funny process with directors, I always think. Every director has his own way of directing. Some of them do a lot of directing – the few English directors I’ve worked with do a lot of directing, and if you can stand that and if you can take that much direction, that works quite well. I, for one, and I don’t know why, but I guess I have a problem with authority figures (laughs), I can’t take too much direction. I like to find my way on my own, and I’m fairly aware of what a director wants in terms of the overall look of his movie. It worked for me – whether it works for the director is hard to tell.”

But there were directors with which Hackman just clicked – Eastwood, Arthur Penn, Tony Scott, all of whom employed him twice. After testing Richard Donner with a refusal to shave off a moustache and go bald for Superman The Movie, he showed loyalty to the director when he was fired from Superman II halfway through filming, by refusing to work for his replacement, Richard Lester. Any footage of Hackman in Superman II was pre-existing stuff shot by Donner.

“When I’m actually on the set or on a stage, actually doing the work, I loved that process and I loved the creative process of trying to bring a character to life.”

That quality, that depth, that ability to adhere to good old-fashioned values is just one reason why Hackman was Hollywood’s go-to guy for men of stature. He played God once. He could go toe-to-toe with the Man of Steel. Heck, he even played the President of the United States twice, first for Eastwood in Absolute Power, and the second time in, well, Welcome To Mooseport.

Frankly, he has been missed – the mouth waters when you begin to imagine what a director like, say, Paul Greengrass could do with Hackman – but the feeling is by no means mutual… even if he does tend to lapse into the present tense when discussing his acting past. “When I’m actually on the set or on a stage, actually doing the work, I loved that process and I loved the creative process of trying to bring a character to life,” he says. “And then, when you’re actually shooting or performing, there is a kind of a feeling that comes over you, a confidence and kind of a wonderful, washed-over feeling of wellbeing, if you will. When it’s going well!

“Whereas the business part of show business is kinda wicked. You jump from trying to be a sponge, if you will, in terms of input from other actors and the director and everything that’s surrounding you, you jump from that to a luncheon meeting with an agent and a producer on another film, or something that’s gone on on the film that you’re doing. It’s kind of a frying pan. It was jarring and at my age and with my health, I decided I didn’t want to do that any longer.”

Which doesn’t mean that he’s averse to the idea of a movie version of Escape From Andersonville, or any of his novels. He’d just rather not be involved in them, thank you very much. And, budding producers or screenwriters, if you think you’re the one to change the mind of the redoubtable Gene Hackman; if you think you’ve got the perfect script with the perfect part to lure him out of retirement – maybe even give him the chance to go for the Oscar hat-trick – here’s some advice for free: don’t bother.

“The agents don’t want me to say it, in case something good comes along,” says Hackman. “But I’m officially retired. No doubt about it.”

Has Hollywood got the message, we ask. “I haven’t talked to Hollywood much lately, so I don’t really know,” says Hackman. “But I would guess that they’ve moved on.”

That’s a shame, says Empire. And, for the last time, Gene Hackman laughs his contented Lex Luthor laugh. “I don’t think so,” he says, simply. And when Gene Hackman says something, you know that he goddamn means it.

Originally printed in Empire in 2009.